Have you ever wondered about the Bible's journey through history, and perhaps, how many books were removed from the Bible? It's a question many people ask, and it gets right to the heart of how different Christian traditions came to have their unique collections of sacred writings. What we call the Bible today, you know, hasn't always looked exactly the same throughout the centuries. It's a story with lots of twists and turns, involving different communities and their choices about what to include.

For many, the Bible feels like a single, unchanging collection, a fixed set of divine messages. Yet, when you start to look at its past, you find a fascinating picture of texts being gathered, debated, and sometimes, shifted around. It’s almost like a library that grew over time, with various librarians deciding which scrolls belonged on the main shelves and which might be placed in a special section, or perhaps, not included at all. This process, it’s fair to say, was quite a long one, not just a quick decision made overnight.

So, what exactly happened to certain books? Were they truly "removed," or was it more about different groups making different choices over time? This article will walk you through some key moments and reasons behind the varying contents of Bibles you might find today. We'll explore the historical discussions and the people who played a part in shaping these very important collections of writings, and you might be surprised by some of the things we discover, too.

Table of Contents

- What Exactly is a "Bible Book," Anyway?

- Early Collections and the Deuterocanonical Books

- Martin Luther's Concerns About New Testament Books

- Key Councils and Canon Decisions

- The King James Version and Its Evolving Contents

- Why Some Books Were Set Aside

- Variations You Might Still Find

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Exactly is a "Bible Book," Anyway?

When we talk about a "book" in the Bible, you know, we're really just referring to one of the many distinct sections. It's like a chapter, but a really big one, that's what it is. These named divisions make up both the older parts and the newer parts of the sacred writings, so it's a way of organizing things, you see. Each of these "books" tells a piece of a larger story, whether it's history, poetry, prophecy, or letters, and they are all quite unique in their style and purpose. Basically, it’s the way the whole collection is divided up, so that’s what we mean by a book, more or less.

So, when we discuss books being "removed," we're talking about these individual, named sections. It’s not like pages were torn out of a single volume; rather, entire sections were either included or not included in different versions of the Bible over time. This makes the question of "removal" a bit more nuanced than it might first appear, as a matter of fact. It’s more about the collective agreement, or lack thereof, on which specific writings belonged in the official list for a particular group of believers.

Early Collections and the Deuterocanonical Books

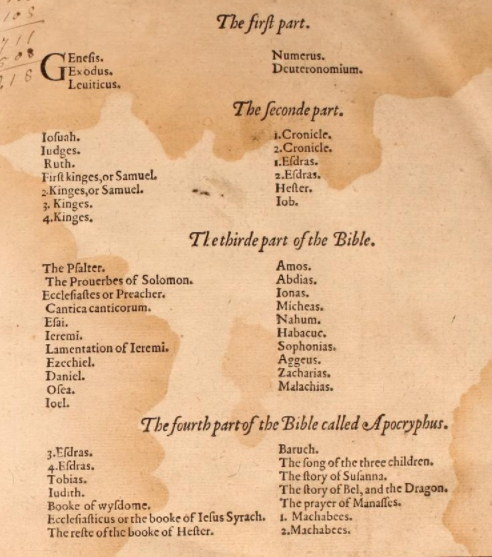

To really get a grip on how many books were removed from the Bible, we need to go back to some of the earliest collections. The Septuagint, for instance, was an early Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures, and it included several books that were not part of the Hebrew Bible. These specific writings are what we often call the Deuterocanonical books, and they have a rather interesting history, you know. They were certainly present in that very important Greek version, which was widely used by early Christians.

However, the Hebrew Bible, which Jewish communities primarily used, did not include these particular books. This difference, right from the start, set up a distinction that would carry through the centuries. So, while early Christian groups often read and valued these Deuterocanonical texts, the Jewish tradition, particularly the Masoretic Jews, wanted those books weeded out. They sought to preserve a collection based on Hebrew originals, and that’s a very key point, too.

Today, you'll find that these Deuterocanonical books are mostly included in the Catholic Old Testament. But, interestingly enough, they are not typically found in the Protestant Old Testament. This is one of the clearest examples of how different Christian traditions came to have slightly different Bibles. It’s almost like two different branches grew from the same tree, each with its own preferred set of texts, in a way. This distinction has been a part of the religious landscape for a very long time, actually.

Martin Luther's Concerns About New Testament Books

It's not just the Old Testament where discussions about which books belong have happened. As a matter of fact, while researching an answer to a different question, it came to light that Martin Luther, a central figure in the Protestant Reformation, had some strong opinions about certain New Testament writings. He apparently attempted to remove Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation from the Bible. This is a pretty significant point, you know, as it shows that even within the New Testament, there were debates.

If this is true, then what were his reasons for doing so? Luther's main concern was how well a book preached "Christ alone" and "faith alone." For instance, he famously called the book of James an "epistle of straw" because he felt it emphasized works too much, rather than faith, which was a core principle for him. He believed that the message of salvation through faith was somewhat clouded in James, and that’s why he had reservations, really. He felt that some of these books didn't quite align with his central theological insights, so he expressed his concerns, you see.

His attempts, however, were not ultimately successful in removing these books from the Protestant canon entirely. While his personal views were well-known and certainly influential, these books remained part of the New Testament for the vast majority of Protestants. It just goes to show that even a very powerful figure like Luther couldn't single-handedly change what was accepted by a wider consensus, so that's a key takeaway here, too. His concerns, though, highlight that the process of canonization was not always smooth or without strong personal opinions, in some respects.

Key Councils and Canon Decisions

So, how many books were decided at the Council of Rome in 382, the Council of Carthage in 397, and the Synod of Hippo in 393? These early church gatherings played a really important part in formalizing the list of books for the Christian Bible. These councils, in a way, represented significant moments where church leaders discussed and affirmed which books were considered authoritative and inspired. They were trying to bring some order and agreement to the collection of sacred texts, you know, for the whole church.

At these councils, a consensus began to form around the 73 books that are found in the Catholic Bible today. Were exactly all 73 books of the Catholic Bible declared canon at these specific meetings? While these councils certainly affirmed the vast majority of these books, the process was more of a gradual acceptance and affirmation over time, rather than a single, sudden declaration. These gatherings were key milestones in that process, solidifying what was already widely accepted in many Christian communities, you know, as a matter of fact. It wasn't a brand-new invention, but a recognition of what was already being used and revered.

The decisions made at these councils provided a strong framework for the biblical canon for centuries, especially within Western Christianity. This helped to create a sense of unity regarding the scriptures that believers could rely on. It’s pretty clear that these historical moments were vital for the eventual shape of the Bible for a very large part of the Christian world, and that’s quite a significant thing to remember, too.

The King James Version and Its Evolving Contents

The King James Version (KJV) of the Bible, published in 1611, is a really famous and historically important translation. Interestingly, the original 1611 KJV actually included the Apocrypha, which are those Deuterocanonical books we talked about earlier. They were right there, printed between the Old and New Testaments. This might surprise some people who are familiar with modern Protestant Bibles, you know, because they often don't have these books anymore.

However, these books were removed by Protestants, particularly those of the Calvinist variety, in the 1700s. This was a deliberate decision that reflected a growing theological stance within certain Protestant groups to align their Old Testament more closely with the Hebrew Bible's canon. Since then, it’s rare to find Protestant Bibles with the Apocrypha, especially in the US anyway, but you can still sometimes find older editions or specialized study Bibles that include them. It's almost like a quiet change that happened over time, becoming the norm for many Protestant traditions, you see.

This change highlights how the contents of the Bible could shift even within a specific translation tradition. It wasn't a sudden, universal removal, but a gradual process influenced by theological preferences and the desire to standardize the Protestant canon. So, while the KJV initially had these books, they slowly faded out of common use in Protestant circles, which is quite a historical point, too. It shows that even beloved versions of the Bible can change over time, and that’s a rather interesting thing to consider, actually.

Why Some Books Were Set Aside

The question of why some books were set aside is a big part of understanding how many books were removed from the Bible. One key reason, as mentioned, comes from the Masoretic Jews. They really wanted those books weeded out that didn't have a clear Hebrew origin. This preference for Hebrew originals became a strong influence, particularly after the Hellenization period, when Greek culture and language were very widespread. So, the other Greek books were removed, those without Hebrew origin, you know, particularly after that time.

This emphasis on Hebrew origin meant that texts like the Deuterocanonical books, which were primarily preserved in Greek, faced more scrutiny from certain groups. It wasn't necessarily about their content being wrong, but more about their linguistic and historical lineage. It's like saying, "We prefer the original language texts," and that's a very understandable position, too. This distinction became a major factor in what was considered "canon" by different religious communities, and it’s still something that shapes Bibles today, in some respects.

Another point is that some of these books would not be translated into Syriac, another important ancient language for Christian scriptures, until the 6th century. This shows that their acceptance and circulation varied significantly across different linguistic and geographical regions. The process of deciding which books belonged was not uniform or instant across the entire early Christian world. It was a long, often debated journey, and that’s something to keep in mind, too. It just goes to show how much variety existed in those early days, you see.

Variations You Might Still Find

Even today, if you look at various Bibles, you might notice some differences in their contents, and that's quite a thing to observe, really. For example, some Bibles have all four Maccabees books, while others don't include any of them. Similarly, some Bibles have Esdras and Wisdom, and yet others don't have these particular texts. This variety shows that even with historical councils and decisions, there isn't always one single, universally agreed-upon list that everyone follows, and that’s a pretty interesting point, too.

If there was an agreement on what books would be included, you might wonder why these variations still exist. The answer is that different Christian traditions and even different publishers have made their own choices over time, based on their understanding of historical authority and theological significance. It’s not about removing books in a negative sense, but rather about different communities defining their own "closed canon" based on their specific heritage and beliefs. This ongoing variety is a testament to the rich and complex history of the Bible's formation, you know, and how different groups have interpreted what truly belongs.

So, when you pick up a Bible, remember that its contents are the result of centuries of discussion, translation, and communal acceptance within specific faith traditions. The question of "how many books were removed from the Bible" leads us to a fascinating story of discernment and historical development, rather than a simple act of deletion. It’s a very human story, too, about how people have sought to preserve and transmit what they believe to be sacred writings, and that’s a rather important aspect to consider, too.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are some common questions people often have about this topic:

Why were books removed from the Bible?

Books weren't so much "removed" as they were either included or not included based on different historical and theological understandings within various religious traditions. For Protestants, a key reason for not including the Deuterocanonical books (often called the Apocrypha) was their lack of Hebrew origin, aligning more closely with the Jewish canon. Martin Luther, too, had specific theological reasons for questioning certain New Testament books, though his views didn't lead to their widespread removal. It was really about different communities making different choices about which books they saw as authoritative, you know.

What are the Deuterocanonical books?

The Deuterocanonical books are a group of writings that are found in the Septuagint, an early Greek translation of the Old Testament, and are included in the Catholic Old Testament. However, they are not part of the Hebrew Bible or the Protestant Old Testament. Examples include books like Tobit, Judith, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Esther and Daniel. These books are considered part of the biblical canon by Catholics and some Orthodox Christians, but not by most Protestants, and that’s a pretty clear distinction, too.

Did Martin Luther remove books from the Bible?

While Martin Luther expressed strong personal doubts and criticisms about certain New Testament books, such as James, Jude, Hebrews, and Revelation, he did not actually "remove" them from the Bible. His translations included these books, though he sometimes placed them at the end with a note about his reservations. His personal opinions were influential, but they did not lead to these books being excluded from the Protestant canon as a whole. So, it’s more accurate to say he questioned them rather than removed them, in a way, you see.

The journey of the Bible's formation is a rich and winding one, showing how different communities have honored and preserved their sacred texts over many centuries. The variations we see today are a reflection of this deep and varied history. To learn more about biblical history and its texts on our site, you can explore other resources. Also, feel free to link to this page for further reading on related topics. For a broader look at the historical texts that shaped early Christianity, you might find it helpful to consult resources like the Encyclopaedia Britannica's entry on Biblical Literature, which offers a good overview of the subject, you know.

Related Resources:

Detail Author:

- Name : Daphnee Koepp

- Username : stuart.marvin

- Email : camylle02@hermann.org

- Birthdate : 2005-10-19

- Address : 9648 Doyle Courts Apt. 508 Port Jedborough, MT 75347-5302

- Phone : +1-901-416-3395

- Company : Smith, Heidenreich and Dibbert

- Job : Anthropologist

- Bio : Voluptatum at voluptatum exercitationem ea iste aut. Non neque ea qui aut. Repellat repellat ut et delectus mollitia voluptatem non. Unde cupiditate quia aut minus.

Socials

tiktok:

- url : https://tiktok.com/@guillermo5334

- username : guillermo5334

- bio : Dolor amet omnis aliquid. Magni tempora neque similique repellat.

- followers : 1144

- following : 480

linkedin:

- url : https://linkedin.com/in/lynch2007

- username : lynch2007

- bio : Sed sint vel et.

- followers : 2519

- following : 92

twitter:

- url : https://twitter.com/guillermo9531

- username : guillermo9531

- bio : Quo et id modi asperiores voluptatem quia repellat. Consequatur nesciunt fuga ipsa nemo optio. Facere quisquam modi voluptatem fugit consequatur.

- followers : 1697

- following : 1097